Discover the 10 essential drill hole types with expert tips and the best drill bits for precise machining and DIY projects.

Ever stared at a project and realised the hole you drilled just wasn’t right? Whether you’re building a machine, crafting furniture, or assembling electronics, understanding the different drill hole types can be a total game-changer. The right hole isn’t just about size—it’s about fit, function, and making sure your fasteners, wiring, or components line up flawlessly. In this guide, you’ll get the lowdown on the most essential types of holes in machining, how to pick the perfect one for your task, and which drill bit to grab next. Let’s cut through the confusion and drill down to precision!

What Defines a Drill Hole: Diameter, Depth, Orientation, Tolerance Levels

At the core of any drilling operation lies the drill hole itself — a simple concept with many critical details. A drill hole is defined by several key factors that determine its function and quality.

Diameter is the hole’s width, which must match the design specifications closely to ensure proper fit or clearance. Even slight deviations can cause issues during assembly or compromise the part’s strength.

Depth determines how far into the material the hole goes. This can be a full penetration through-hole or a partial blind hole. Knowing the precise depth is crucial, especially for threaded holes or multi-step bores.

Orientation refers to the hole’s angle relative to the workpiece. Whether perpendicular or angled, correct orientation ensures components align and fit as intended. Machines and setups must control this carefully to avoid misalignment.

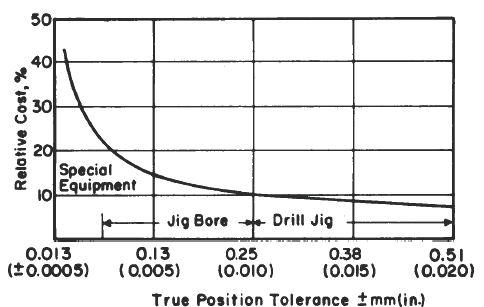

Finally, tolerance levels are the allowable variations in the hole’s diameter, position, and depth. These tolerances are often guided by GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) standards, ensuring parts meet functional requirements without unnecessary production costs.

Understanding these fundamental elements helps create drill holes that perform reliably, whether for fastening, alignment, or fluid passage.

Drilling vs. Other Hole-Making Methods

Drilling is the most common way to create round holes by removing material with a rotating bit. But it’s not the only method—you also have options like boring, reaming, EDM, and laser cutting, each with its own strengths and ideal uses.

- Drilling is great for initial hole-making, especially when you need variable depths and diameters quickly. It cuts material for most through holes, blind holes, and threaded holes.

- Boring comes after drilling when you need more precision or a larger diameter. It refines the hole’s size and finish by removing small amounts of material with a single-point cutting tool.

- Reaming is a finishing step used to improve hole tolerance and surface smoothness. Reamers give a tighter diameter control than drilling alone but depend on a pre-drilled hole.

- EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining) uses electrical sparks to remove metal without physical contact. It’s ideal for very hard, thin, or delicate materials where traditional drilling can cause damage or stress.

- Laser drilling Offers precision and speed for tiny holes, especially in thin metals or plastics. It’s non-contact and can produce holes with minimal heat-affected zones, but not suitable for all materials or deeper holes.

Understanding these differences helps choose the right hole-making process depending on your material, hole purpose, and precision needs. For example, if you’re working on aluminium or titanium parts, the transition from drilling to boring can improve accuracy—check out our detailed comparison of titanium vs. aluminium strength to select the appropriate material and hole-making strategy.

Common Challenges and Solutions in Drilling

Drilling isn’t as simple as spinning a bit and pushing it into the material. Some common challenges arise that can affect quality and tool life if not managed properly.

Chip Evacuation

When a drill cuts, it produces chips that need to be cleared quickly. If chips clog the hole, they cause friction and can even break the bit. To prevent this:

- Use proper flute design on drill bits for better chip removal

- Employ peck drilling—a technique that periodically retracts the bit to clear chips

- Utilise air or coolant blasts to wash away debris

Vibration Control

Vibrations (or chatter) lead to rough holes and faster tool wear. Reduce vibration by:

- Securing the workpiece firmly

- Using sharp, well-maintained drill bits

- Selecting the correct spindle speed and feed rates based on material and hole size

Heat Buildup

Heat is the silent enemy in drilling. Excessive heat softens the bit and affects hole accuracy. Keep temperatures down by:

- Applying adequate coolant or cutting fluid to the drilling zone

- Using high-quality drills with coatings like TiN or carbide for better heat resistance

- Avoiding excessive feed rates that increase friction

Coolant Workflows

Effective coolant delivery is crucial. Poor coolant flow leads to chip welding and thermal damage. Tips for efficient coolant use:

- Ensure coolant reaches the cutting edge directly, especially in deep holes

- Use the right coolant type (oil-based or water-based depending on material)

- Regularly check and maintain coolant pressure and flow systems

Addressing these challenges upfront not only improves hole quality but saves time and tool costs. For machining specialty materials like aluminium or magnesium, following coolant and vibration advice is even more critical—you can find more on safe machining techniques in our expert guide to machining magnesium safely.

Keeping these factors in check ensures your drilling process is smooth, accurate, and efficient every time.

Fundamentals of Drilling: Pro Tip – Reference GD&T Standards in Technical Drawings

When planning any drilling operation, always reference GD&T (Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing) standards on the technical drawings. These standards define the exact size, form, orientation, and allowable variation of holes, which helps ensure your drilled holes meet design intent and function properly.

Key benefits of following GD&T for drill holes:

- Consistent communication: Everyone on the shop floor is on the same page regarding hole tolerances.

- Better fit and function: Proper hole size, position, and tolerance reduce assembly issues.

- Improved quality control: Inspectors can quickly verify if the hole meets specifications using precise measurement methods.

Ignoring GD&T details can lead to out-of-spec holes, causing part rework or failure.

For modern machining projects, including large casting sets, integrating GD&T details early enhances overall process efficiency and quality. You might also find value in understanding related concepts like proper helix pitch formulas in drill bits to improve drilling accuracy and finish. For more precision finishing tips, check out our guide on mechanical polishing techniques and best practices for precision finishing.

Through Holes: Full Penetration, Uses, Associated Bits

Through holes are drill holes that completely pass through a material, creating an open path from one side to the other. These holes are essential when you need to secure fasteners like bolts or screws that extend fully through a part, allowing nuts or washers to attach on the opposite side. Because they go all the way through, through holes also simplify chip evacuation and reduce heat buildup during drilling.

Common uses include assembly components, mounting brackets, and parts where clearance for fastening hardware is required. Standard drill bits like twist drill bits are typically used for through holes, selected according to the desired diameter and material being drilled. For metal, high-speed steel (HSS) or carbide bits offer durability and precision. When working with wood or softer materials, brad-point bits or Forstner bits may be more appropriate to ensure clean entry and exit holes.

For precision through holes, it’s useful to consider the diameter and tolerance requirements upfront—this ensures a proper fit for fasteners and prevents alignment issues downstream. If you’re aiming for tighter tolerances or smoother finishes, exploring reaming as a follow-up process can be beneficial. For more on matching hole-making tools with precision needs, check out our guide on types of reamers explained for precision machining and tool selection.

Blind Holes: Partial Depth, Use Cases, and Bit Selection

Blind holes are drill holes that do not go all the way through the material—they have a defined partial depth. These holes are common when you need to avoid breaking through the surface on the opposite side, such as in housings, engine blocks, or precision components. Because a blind hole stops before reaching the far side, chip evacuation can be tougher, increasing the risk of bit breakage if not managed properly.

Typical uses include threaded holes where external exposure isn’t desired, or holes for press fits and inserts in sensitive parts. When drilling blind holes, using specialised drill bits like reduced flute or parabolic flute bits improves chip removal and reduces heat build-up. Peck drilling is also recommended to clear chips incrementally.

Common blind hole bits:

- Reduced shank twist drills for better chip clearance

- Spot drill bits for accurate starting without wandering

- Parabolic flute bits for deep blind holes in metal

For reliable results, always check your depth control settings and coolant flow. If you want more guidance on precision hole-making, the detailed master drilling holes guide offers great tips suited for varying materials and hole types.

Threaded (Tapped) Holes: Internal Threads, Metric vs. UNF, Torque Specs, Tool Bits

Threaded or tapped holes are drilled holes with internal threads cut inside to accept screws or bolts. These holes allow for strong, reusable fastenings without needing a nut on the other side.

Key Points for Threaded Holes:

- Internal Threads: Created using a tap tool after the hole is drilled to the correct diameter (called the tap drill size).

- Metric vs. UNF Threads:

- Metric threads are common internationally and measured in millimetres (e.g., M6, M8).

- UNF (Unified National Fine) threads are standard in the United Kingdom, identified by threads per inch (e.g., 1/4″-28 UNF).

- Torque Specs: Proper torque values depend on thread size, material, and thread class. Over-tightening can strip threads; under-tightening risks loosening.

- Tool Bits: Use high-quality taps—hand taps for manual work, machine taps for CNC operations. Coated carbide taps work great for metals like aluminium or steel, and stepped or spiral flute taps assist with chip evacuation in blind holes.

Always machine the correct hole size before tapping and reference GD&T hole tolerances to ensure fit and function. For precise assembly, using correctly threaded holes reduces the risk of thread failure and improves fastener longevity.

For advanced precision in fastening, explore master guides on interference fits to understand how tapped holes interact with bolts during assembly.

Clearance Holes: Oversized for Fastener Passage

Clearance holes are drilled larger than the fastener’s outer diameter to allow screws, bolts, or pins to pass through smoothly without threading into the material. These holes simplify assembly by giving fasteners enough room for easy insertion and alignment.

Common Clearance Hole Types:

- Standard Clearance Holes: Sized just above the fastener diameter.

- Close Clearance Holes: Slightly larger but tighter fit for better control.

- Free Clearance Holes: Much larger than the fastener, often for loose fit or tolerance adjustments.

Benefits:

- Speeds up assembly by avoiding binding.

- Prevents damage to threads during installation.

- Allows for slight misalignment without straining components.

Recommended Drill Bits:

- Twist Drill Bits: Most common for general clearance holes in metals and plastics.

- Cobalt or Carbide Bits: For tougher materials needing precision and durability.

- Step Drill Bits: Great for creating multiple clearance sizes quickly in thin materials.

When planning clearance holes, always check the fastener specs and apply the proper hole diameters according to industry standards to ensure smooth assembly and durable joints. For best practices on hole tolerances and tapping, referencing GD&T standards or using precision tools can save time and costs.

For more on precision tool selection and hole standards, see our guide on best lathe cutters for precision turning.

Core Types of Drill Holes: Countersunk Holes

Countersunk holes have a conical recess designed to allow screw heads to sit flush with or below the surface of the material. This makes them ideal for applications where a smooth finish is critical, such as in furniture, metal assemblies, and aerospace components.

Key Points About Countersunk Holes:

- Shape: Typically conical, matching the screw head angle.

- Standard Angles: Most common are 82°, 90°, and 100°, depending on the screw type.

- Purpose: Prevents protruding screw heads, improving aesthetics and reducing snag risks.

- Applications: Used in sheet metal, woodworking, and precision machinery parts.

For best results, use dedicated countersink drill bits or combination bits that drill and countersink in one step. Proper angle matching prevents damage to the screw and material.

Countersunk holes must be designed with correct depth and diameter tolerance, following GD&T hole standards to ensure consistent screw seating and reliable assemblies. If you’re working with aluminium parts requiring surface finishes or anodising, pairing countersunk holes with processes like the aluminium anodising guide helps maintain durability and appearance.

Counterbored Holes: Cylindrical Enlargement for Bolt Heads

Counterbored holes have a larger cylindrical section at the top part of the hole, designed specifically to seat bolt heads or nuts flush with or below the surface. This shoulder created by the counterbore gives a solid seating area, ensuring better load distribution and alignment of fasteners in assemblies.

Unlike spotface holes, which are shallow and mainly used to create a flat surface on rough or uneven material, counterbores are deeper and sized precisely to fit standard bolt heads or washers. This makes counterbored holes essential when fastening hardware needs a stable, recessed seat.

Counterbore drill bits usually have a pilot tip to guide the cut and maintain concentricity with the rest of the hole, which is crucial for proper alignment and torque performance in bolts. These holes are common in machinery, automotive, and structural applications where flush mounting is required.

For detailed machining practices and precision setups, checking out guides on CNC milling precision can help optimise your counterboring process.

Spotface Holes: Shallow Flat-Bottomed for Seating on Uneven Surfaces

Spotface holes are shallow, flat-bottomed recesses designed to create a smooth, level seating area on uneven or rough surfaces. Unlike deeper holes, these require minimal material removal and are often used to ensure fasteners like bolts or screws sit flush and secure without rocking.

Common in machining and assembly, spotfacing helps improve load distribution and alignment, especially on castings or rough-milled parts. It’s important to distinguish spotface holes from counterbore holes: spotfaces are typically shallow and just enough to create a clean contact surface, while counterbores are deeper and sized to fit bolt heads or nuts.

Using the correct drill bit—often a spotface cutter or counterbore tool—ensures precision and prevents damage to the underlying material. This approach supports better joint reliability and can be critical in both metal and plastic parts, such as in automotive plastic components, where uneven surfaces are common.

For more on machining precision and tooling, you might find our guide on precision tooling manufacture helpful.

Interrupted (Segmented) Holes

Interrupted or segmented holes are a series of drilled sections separated by intentional gaps. Instead of one continuous bore, these holes consist of multiple short holes spaced apart. This design often appears in applications requiring partial penetration or where weight reduction and airflow are critical, such as in aerospace or lightweight structural parts.

Key Challenges

- Alignment: Because you’re essentially drilling multiple distinct holes, maintaining perfect alignment is tricky. Misalignment can cause assembly issues or weaken the part.

- Tooling: Specialised fixtures or CNC programming ensure each segment lines up exactly. Precision machines and careful setup are essential to maintain consistent spacing and position.

Interrupted holes differ from typical through or blind holes by the segmented design, so traditional drill bits and methods won’t always suffice. Often, customised tooling or modular drill bits are used to achieve correct spacing and avoid tool wear.

If you want to ensure your drilling meets high precision and fit standards, integrating this with GD&T hole tolerances can help streamline your technical drawings and quality checks.

Core Types of Drill Holes: Multi-Step (Stepped) Holes

Multi-step or stepped holes feature variable diameters within a single bore, created by drilling sections of different sizes one after another. These transitions can accommodate multiple components in one hole or provide seating for various fasteners and fittings. Stepped holes are especially useful in assemblies where clearance, threading, and bearing surfaces need to coexist precisely.

Common uses include:

- Housing for shoulder bolts where the larger diameter allows bolt heads to sit flush

- Creating pilot hole sections combined with counterbores or threaded sections

- Accommodation of press fits in one part and clearance fits in another

Machining stepped holes requires careful measurement and control to ensure smooth transitions and accurate depths. Tool changes often involve swapping drill bits or using specialised step drills. Understanding the required dimensions and tolerances upfront helps avoid re-machining.

For materials like aluminium alloys, which are common for stepped hole applications, incorporating tailored cutting strategies from resources on aluminium machining offers efficiency and precision. Check out guidance on aluminium alloys machining for tips specific to these metals.

In short, stepped holes allow you to combine multiple hole features in one bore, saving space and enhancing assembly integrity when designed and executed properly.

Oversized and Undersized Holes

Oversized and undersized holes are essential when precise tolerance adjustments are needed, especially for press fits and clearance fits in assemblies. An oversized hole is intentionally drilled larger than the nominal diameter to enable parts to slide or fit easily — common in clearance holes where fasteners pass through without friction. Conversely, an undersized hole is slightly smaller, often used as a starting point for tapping threads or creating a tight interference fit.

Both types rely heavily on ISO tolerance classes, which specify allowable size variations depending on the required fit—whether loose, sliding, or press-fit. For example, in press fit applications, an undersized hole matched with an oversized shaft ensures a secure, slip-free connection.

Applications include:

- Press-fit bearings, bushings, and shafts

- Pilot holes for threading or reaming

- Clearance holes for smooth bolt or pin assembly

Keep in mind the impact of tolerances on machining costs and inspection requirements, as tighter fits demand higher precision. Using proper drill bits and calibration prevents common issues such as hole deformation or excessive wear. For detailed guidance on hole tolerances and inspection, incorporating GD&T hole tolerances in your drawings ensures accuracy on the workshop floor.

For related best practices in coolant selection to maintain tool life during tight tolerance drilling, check out this comprehensive machining coolant guide.

Drill Bits Matched to Hole Types: Overview Table

Choosing the right drill bit for your hole type is key to accuracy and tool life. Here’s a simple overview matching common drill hole types to the best drill bit styles, materials, and typical sizes:

| Hole Type | Recommended Drill Bit | Common Materials | Typical Sizes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Through Hole | Standard Twist Drill | Metal, wood, plastics | 1/16″ to 1″ (custom sizes) |

| Blind Hole | Spur-Point or Parabolic | Metals, alloys | Smaller diameters, varied depths |

| Threaded (Tapped) | Drill + Tap (Taper or Plug) | Steel, aluminium | Drill bit slightly smaller than thread size |

| Clearance Hole | Oversized Twist Drill | Metals, wood | Standard fastener clearances |

| Countersunk Hole | Countersink Drill Bit | Wood, metal | 82°, 90°, 100° angles common |

| Counterbored Hole | Counterbore Drill Bit | Metals | Match bolt head sizes |

| Spotface Hole | Spotfacing Bit or End Mill | Metals | Slightly larger than fastener |

| Interrupted Hole | Custom or Specialised Bits | Metals, composites | Variable, depends on segmentation |

| Multi-Step Hole | Step Drill Bit | Thin metals, plastics | Multiple diameters in one bit |

| Oversized/Undersized Hole | Reamer or Oversized Twist | Metals | Precision fit classes (H7, etc.) |

Material Notes:

- Carbide bits work best for hard metals and high-volume jobs.

- High-speed steel (HSS) bits are versatile, ideal for general metal and wood.

- 砖石钻头 have carbide tips and are made for concrete or stone.

- For plastics and wood, brad-point or Forstner bits offer cleaner holes with less tear-out.

Selecting bit size also depends on following design specifications, including hole tolerance and final fit, which ties into Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) standards. For a deeper dive into hole tolerances, consider checking out our detailed guide on types of tolerancing explained.

Matching the right bit to your hole type and material is the first step in clean, precise, and efficient hole making.

Drill Bits Matched to Hole Types: Material-Specific Guidance

Choosing the right drill bit depends heavily on the material you’re drilling into. Using the wrong bit can lead to poor hole quality, faster wear, or even bit failure. Here’s a quick guide for common materials:

- Wood: Use spade bits, brad-point bits, or Forstner bits for clean, precise holes. These bits reduce splintering and provide flat-bottom holes ideal for furniture or cabinetry.

- Metal: Twist drill bits made from high-speed steel (HSS) or cobalt are best. For harder metals, carbide drill bits are recommended to maintain sharpness and resist heat. Carbide bits ensure longer life when drilling stainless steel, cast iron, or other tough alloys.

- Masonry: Masonry bits have a tungsten carbide tip and a flute design that handles concrete, brick, and stone. Use hammer drill settings with these bits for better chip removal and faster drilling.

- Plastics: Standard twist bits work fine, but drill slower to prevent melting or cracking. Specialised bits with sharper points are available for some plastics to reduce chipping.

Matching your bit to the right material ensures cleaner holes, longer bit life, and safer, more efficient drilling. For a deeper dive on drilling precision, especially with hard-to-machine materials, check out this guide on mastering blind holes design and machining techniques for precision.

Drill Bits Matched to Hole Types: Advanced Options

When working with different drill hole types, advanced drill bits can boost precision and efficiency. Here’s a quick look at key options:

| Drill Bit Type | Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Exchangeable-Tip Bits | Replaceable cutting tips, cost-effective | Large diameter holes, reduces waste |

| Solid Carbide Bits | Extremely hard, wear-resistant | High speed, tough materials like hardened steel or stainless |

| Peck Drilling Bits | Special geometry for chip breaking | Deep hole drilling, prevents clogging and overheating |

Exchangeable-Tip Bits are great when you need large holes but want to avoid buying and replacing entire bits. Swapping worn tips is quick and economical, especially for repetitive tasks.

Solid Carbide Bits shine with high durability and stability. They deliver tight tolerances at fast cutting speeds, ideal for metals requiring clean holes with minimal wear.

Peck Drilling is a technique more than a bit type—it uses short repeated drill advances and withdrawals. This method helps clear chips effectively and reduces heat, which is crucial for deep holes or materials prone to clogging.

Combining these advanced bits with the right drilling approach gives you better finishes, longer tool life, and consistent hole quality every time. For metal parts manufacturing, using solid carbide bits and incorporating peck drilling can dramatically improve productivity.

For more on precision manufacturing benefits, you might find this guide on die cast zinc benefits and precision manufacturing parts helpful in understanding how drill choices influence quality outcomes.

Drill Bits Matched to Hole Types: Vast Recommendation for High Tolerance

When it comes to precision drilling, carbide twist bit sets stand out as the go-to option for high tolerance work. These bits are crafted from solid carbide, which offers exceptional hardness and wear resistance, making them perfect for maintaining tight dimensional accuracy in metals and composites.

Why choose carbide twist bits for high tolerance holes?

- Durability: They last longer than high-speed steel bits, reducing tool changes and downtime.

- Precision: The rigid carbide minimizes deflection, ensuring straighter, cleaner holes.

- Versatility: Ideal for drilling materials like stainless steel, aluminium, and engineering plastics.

- Heat resistance: Carbide bits handle higher temperatures without losing sharpness, crucial for maintaining tolerance under challenging conditions.

If your project demands clean, consistent holes with minimal rework, investing in a quality carbide twist bit set is wise. They work well with advanced drilling methods like peck drilling to manage chip removal and reduce heat buildup.

For more insight on machining metals like aluminium, check out our detailed comprehensive aluminium alloys chart guide with properties and uses. This resource helps you match drill bits to specific metals for optimal results.

In , carbide twist drill bits combine toughness and precision, making them the vast recommendation for anyone focused on high tolerance drilling in industrial and precision manufacturing settings.

Step-by-Step: How to Select and Machine the Right Drill Hole Type – Workflow

Selecting and machining the right drill hole type requires a clear, organised workflow to ensure accuracy and efficiency. Here’s a straightforward process to follow:

1. Design Analysis

- Review the Technical Drawings: Focus on hole dimensions, depths, orientation, and tolerance levels. Use GD&T standards to understand geometric requirements—this prevents costly errors during machining.

- Understand Functional Needs: Determine if the hole is for fastening, clearance, threading, or seating a bolt head, as this affects hole type and bit choice.

2. Hole Type Selection

- Choose between through holes, blind holes, threaded holes, clearance holes, countersunk, or specialised types based on design specs and application. Consider the material you’re working with and the hole’s final use.

3. Bit and Machine Selection

- Match the drill bit to the hole type—twist bits for general drilling, carbide bits for hard metals, or specialised bits like countersink or spotface bits. Select machine tools capable of handling the hole depth and precision required.

4. Preparation

- Securely set up your workpiece to prevent vibration or movement. Check machine calibration and the sharpness of the drill bit. Use pilot holes if necessary for accuracy, especially with larger diameters or harder materials.

5. Drilling

- Use appropriate speeds and feeds according to the material and type of drill bit. Apply coolant or lubrication to control heat build-up and facilitate chip removal. Employ peck drilling for deep holes to prevent tool wear and maintain hole quality.

6. Inspection

- Measure the hole diameter, depth, and surface finish against the design specifications. Use gauges or coordinate measuring machines (CMM) when precision is critical. Double-check threaded holes with tap gauges.

Following this workflow ensures your drilled holes meet functional and quality standards, reducing risks such as drill bit breakage or misalignment. For deeper insights into machining defect-free components, you might find this guide on seamless castings very helpful to understand manufacturing precision.

Case Study: Drilling a Threaded Blind Hole in Aluminium — Common Errors and Solutions

Drilling a threaded blind hole in aluminium requires precision to avoid costly mistakes. Here is a straightforward step-by-step overview of typical errors and how to correct them:

Common Errors

- Incorrect Drill DepthDrilling too deep can break the drill bit or damage the tap. Too shallow results in incomplete threads.

- Using the Wrong Drill Bit SizeThe pilot hole must match the tap drill size for the thread’s pitch and diameter. A bit that is too large or too small causes thread failure.

- Poor Chip EvacuationAluminium chips can clog the hole, causing heat build-up and drill wear.

- Incorrect Tap AlignmentMisaligned taps damage threads and increase the risk of tool breakage.

- Inadequate LubricationLack of cutting fluid leads to heat, poor finish, and rapid tool wear.

How to Fix Them

- Measure and Mark Drill DepthUse a drill stop or tape to control the exact drilled depth according to thread specifications.

- Refer to Tap Drill ChartsFor aluminium, select the correct pilot drill size based on the thread—metric or UNF. You can find detailed guides like this how to tap thread properly for assistance.

- Use Compressed Air or Coolant; Clear chips frequently and apply proper cutting fluid designed for aluminium to reduce heat.

- Ensure Proper Tap Alignment; Use a tapping guide or machine to keep the tap straight during threading.

- Apply Appropriate Lubricants; Use aluminium-specific tapping fluids for smoother cuts and longer tool life.

Following these tips reduces errors and improves the quality of threaded blind holes. Precision in drilling combined with the right tapping approach ensures a reliable, durable thread every time.

Safety Protocols: PPE, Chip Management, Avoiding Drill Wander

When selecting and machining the right drill hole type, safety should always come first. Here are the key safety protocols to keep in mind:

- Wear Proper PPE: Always use safety glasses or goggles to protect your eyes from flying chips. Hearing protection is recommended during prolonged machine use, and gloves can help handle sharp tools—just avoid loose gloves that can snag on rotating parts.

- Manage Chips Effectively: Clear chips frequently to prevent clogging, which can cause tool damage or workpiece burns. Use appropriate coolant or compressed air to flush chips away, especially during deep hole drilling or when working with metals.

- Avoid Drill Wander: Drill wander occurs when the bit slips off the intended spot, leading to inaccurate holes and potential tool breakage. To prevent this:

- Start with a pilot hole or centre punch to guide the bit.

- Maintain steady feed rates without forcing the drill.

- Use sharp, properly sized bits matched to the hole type.

- Secure the workpiece firmly to minimise vibrations.

Adhering to these safety steps not only protects you but ensures cleaner, more precise holes. Incorporate these practices into your workflow for safer and more efficient drilling operations. For additional insights on tool selection and machining, check out our guide on types and uses of end mills.

Tolerance Deep Dive: Fits, Classes, and Their Impact on Quality and Cost

When drilling holes, understanding tolerance and fit classes is key to getting the part right. Tolerance defines how much a hole’s size can vary from its nominal dimension. Fits describe the relationship between the hole and its mating part—whether it’s loose, tight, or somewhere in between.

Common Fit Types

- Clearance Fit: Hole size is larger than the shaft, allowing easy assembly; common in bolts and pins.

- Interference Fit: Hole is smaller or equal to the shaft, creating a press or friction fit for stronger holds.

- Transition Fit: Between clearance and interference, balancing ease of assembly and tightness.

Tolerance Classes

Standards like ISO and ANSI specify tolerance classes for holes and shafts, such as H7 or H8 for holes, which tells you the exact allowable size range. Choosing the right tolerance affects:

- Quality: Tighter tolerances give higher precision but require better control and inspection.

- Cost: Narrow tolerance ranges increase machining time, tooling wear, and scrap rates, raising price.

Why It Matters

Ignoring tolerance needs could lead to:

- Loose parts causing noise or wear

- Jamming assemblies requiring rework

- Higher scrap or warranty claims

For best results, reference GD&T hole tolerances on your drawings and communicate fit requirements clearly to your machinist. This ensures the drilled hole meets function without overpaying for unnecessary precision.

Understanding these tolerance fundamentals will balance part performance with manufacturing efficiency and cost. For more on precise hole finishing, check out our reamer buyer’s guide to help improve hole accuracy post-drilling.

Advanced Considerations: Deep Hole Drilling

Deep hole drilling is a specialised process for creating holes that are significantly deeper than their diameter, often used in industries like aerospace, automotive, and oil & gas. One common method is gun drilling, which uses long, thin drills with a single straight flute designed to efficiently remove chips and control heat in deep cuts.

Key factors in deep hole drilling include:

- Straightness: Maintaining a precise, straight bore is critical. Gun drills are guided by bushings or liners to minimise deviation and ensure the hole’s alignment matches design specifications.

- Vibration Control: Deep drilling can cause tool chatter and vibrations, impacting surface finish and tool life. Using stable machine setups, optimised cutting parameters, and sometimes vibration dampening tools help maintain smooth operation.

- Coolant Flow: Proper coolant delivery is crucial to flush chips and cool the cutting edge deep inside the bore, preventing premature wear and thermal damage.

These advanced techniques improve hole quality and repeatability, essential in high-precision manufacturing. For more on precision hole finishing, check out our complete guide on reamers and hole accuracy.

Advanced Considerations: Sustainability Angle in Drilling

Sustainability in drilling is becoming a priority for many workshops across the United Kingdom. Eco-friendly coolants are a big part of this shift—they reduce environmental impact while extending tool life and improving chip evacuation. Water-based and biodegradable coolants are common alternatives to traditional oil-based fluids, reducing hazardous waste and making cleanup easier.

Another key factor is using recyclable drill bits. Carbide and high-speed steel bits can often be reconditioned or recycled instead of discarded after use. Choosing durable bits designed for long service lives also lowers waste and reduces the costs associated with frequent tool changes.

To optimise sustainable drilling practices:

- Use biodegradable or water-soluble coolants for better environmental outcomes.

- Select drill bits with high wear resistance and recyclability.

- Implement coolant workflows that minimise consumption and contamination.

- Regularly maintain tools and machinery to extend their lifespan.

Focusing on eco-friendly materials and processes not only supports greener manufacturing but can also enhance efficiency and reduce overall operational costs. For deep technical standards that might overlap with sustainable machining, checking guidelines like those related to GD&T hole tolerances helps ensure precision without waste.

Future Trends in Drill Hole Types: AI CNC Paths and Hybrid Laser Drilling

The future of drilling is evolving rapidly, driven by advances like AI-powered CNC paths and hybrid laser drilling. These innovations are making hole-making more precise, faster, and more adaptable to complex materials.

AI CNC Paths

Artificial intelligence is being integrated into CNC drilling machines to optimise tool paths dynamically. This means drilling operations adjust in real-time based on material behaviour, tool wear, and vibration feedback. The result is reduced cycle times, improved hole quality, and longer tool life. Predictive algorithms help avoid common issues like drill wander or uneven chip evacuation, making it easier to maintain tight tolerances—especially important when dealing with complex fit standards covered under GD&T.

Hybrid Laser Drilling

Hybrid laser drilling combines traditional mechanical drilling with laser assistance. The laser pre-weakens or partially penetrates the material, allowing a drill bit to complete the hole more quickly with less force. This technique excels with hard-to-machine metals, composites, or layered materials. It reduces heat build-up and tool wear, helping deliver cleaner holes with smooth finishes. Hybrid drilling also opens new doors for creating micro-holes or complex shapes that conventional drills struggle with.

These future technologies aim to boost efficiency and precision for industries ranging from aerospace to automotive and medical device manufacturing. As these tools and techniques mature, they will reshape how we approach even the most routine drill hole types.

For deeper insight into machining and material choices, consider exploring the Tool Steel Grades Guide and how precision processes can complement advanced drilling methods.

Common Mistakes and Troubleshooting: Top Pitfalls

When working with drill hole types, a few common mistakes can cause big headaches:

- Wrong Bit Selection: Using the incorrect drill bit for your material or hole type leads to poor finishes, faster bit wear, and even breakage. For example, using a standard twist drill on hardened steel instead of a carbide bit can ruin your hole and tool.

- Ignoring Peck Cycles: Peck drilling isn’t just for deep holes. Skipping this can cause chip clogging, heat build-up, and uneven holes. Breaking your drilling process into smaller increments with peck cycles helps clear chips and controls temperature.

- Lack of Deburring: Skipping deburring leaves sharp edges or burrs that affect assembly and part function. It’s a small step that prevents costly rework or part rejection, especially on clearance and threaded holes.

Understanding these pitfalls can save time, reduce costs, and improve hole quality. For more precision, consider following a detailed reaming guide to refine your holes after drilling.

Quick Fixes for Common Drilling Problems

| Problem | Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Drill bit wandering | No pilot hole or dull bit | Use a pilot hole; sharpen or replace the bit |

| Excessive heat buildup | Poor coolant flow or incorrect speed | Improve coolant application; reduce speed |

| Chips clogging the hole | Inefficient chip evacuation | Use peck drilling; clean chips frequently |

| Bit breakage | Incorrect bit for material/depth | Select proper bit; reduce feed rate |

| Hole size out of tolerance | Incorrect bit size or worn bit | Check bit size; replace worn bits; measure often |

| Rough hole surface | Dull bit or too fast feed | Sharpen bit; reduce feed speed |

| Vibration during drilling | Loose setup or wrong tool choice | Tighten clamps; choose appropriate tooling |

Keep these fixes in mind to save time and improve drilling quality in your projects. For help setting up coolant systems and maintaining drill bits, check out our detailed machine coolant guide.

When to Call in Pros: High-Volume, Exotic Alloys, Professional Services

Sometimes drilling tasks exceed the DIY or in-house workshop level, especially when dealing with high-volume production runs or materials that challenge standard tooling. Here are key situations when it’s best to call in professional services:

- High-Volume Jobs: Drilling hundreds or thousands of holes requires consistent precision, quick turnaround, and tool life management that professionals handle better. They bring specialised CNC machines and automation to keep costs down and quality high.

- Exotic Alloys and Difficult Materials: Metals such as titanium, Inconel, or hardened stainless steel require advanced tooling, cooling methods, and specific drill bit geometries. Professional workshops have the experience and equipment to avoid bit breakage and maintain optimal hole tolerances.

- Complex Hole Requirements: When you need deep hole drilling, multi-step or interrupted holes, or tight GD&T tolerances, experts with specialised machines and inspection tools make the difference.

- Troubleshooting Persistent Issues: If you face recurring problems like drill wander, heat build-up, or poor chip evacuation despite best efforts, professional machinists can diagnose and apply advanced solutions.

Outsourcing to professionals ensures quality, repeatability, and minimises downtime—crucial for keeping your project or production line running smoothly. For projects involving aluminium or other common metals, understanding nuanced machining needs can also relate to associated processes like riveted aluminium installation which affect overall assembly and performance.

When you are overwhelmed by drilling complexities, bringing in experts is wise, cost-effective, and prevents headaches later on.