Discover 14 essential types of holes in engineering with detailed symbols, applications, and expert tips for precise machining and design solutions.

Fundamentals of Hole Geometry and Specifications

Understanding hole types starts with the basics of geometry and machining specifications. Every hole is defined by key elements: diameter, depth, tolerance, and surface finish. These factors ensure the hole meets its function and fits with mating parts.

| Element | Description | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Diameter | Width of the hole, usually in inches or mm | Critical for fit and clearance |

| Depth | How deep the hole goes | Determines strength and purpose |

| cURL Too many subrequests. | Acceptable variation in size | Ensures proper fit without tightness or looseness |

| Surface Finish | Smoothness inside the hole | Impacts sealing, threading, and wear resistance |

Next, it’s important to distinguish blind holes from through holes:

- Blind holes stop within the material; they do not go all the way through.

- Through holes penetrate completely, exiting the opposite side.

Each type suits different applications, depending on strength requirements and assembly design.

Machining Basics

Common hole-making processes include:

- Drilling: Fast and rough; creates initial holes.

- Boring: Enlarges and improves hole accuracy.

- Reaming: Smooths and sizes holes to precise dimensions.

- cURL Too many subrequests.: Cuts internal threads.

These operations use tools like twist drills, boring bars, reamers, and taps. Choosing the right tool depends on materials and hole type.

Tip for Complex Geometries

Multi-axis CNC machines allow precise hole making in complex parts. They offer:

- High accuracy

- Ability to drill angled and curved holes

- Reduced setup time

This technology is especially useful for aerospace and medical components where exact geometries are essential.

By mastering these fundamentals, you set a solid foundation for understanding more specialized hole types.

Simple and Basic Holes The Foundation of Machining

Simple holes are the most common type you’ll see in machining. Think of them as plain cylindrical openings with no extra features. These holes usually come with specific symbols on drawings and have established tolerances for diameter and depth to ensure proper fit and function.

Through holes go all the way through the material. They’re easy to machine and ideal for fasteners, pins, or clearance purposes. Because they fully penetrate, they offer straightforward applications like bolt passages or alignment. The standard symbol for these holes shows a clean, full penetration line, and they’re popular for their simplicity and reliability.

Blind holes only go partway through a part. They require careful depth control because stopping at the right point can be tricky. Blind holes are essential when the back side of a workpiece needs to stay sealed or intact, such as in hydraulic components or certain prototypes. The symbol for blind holes highlights the partial depth, making it clear to machinists how deep they need to drill without going all the way through.

Vast Case example: For aluminum prototypes, vast has machined through holes with tight tolerances that ensured perfect fit and function in lightweight parts, demonstrating how critical precision is even in simple holes.

Understanding these simple hole types is key—they form the building blocks of more complex machining processes used every day in U.S.-based manufacturing shops and production lines.

Specialized Fastening Holes For Screws Bolts and Threads

Fastening holes are designed specifically for screws, bolts, and threaded fasteners. One common type is the cURL Too many subrequests., cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests. cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests. cURL Too many subrequests.

Pro tip: cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

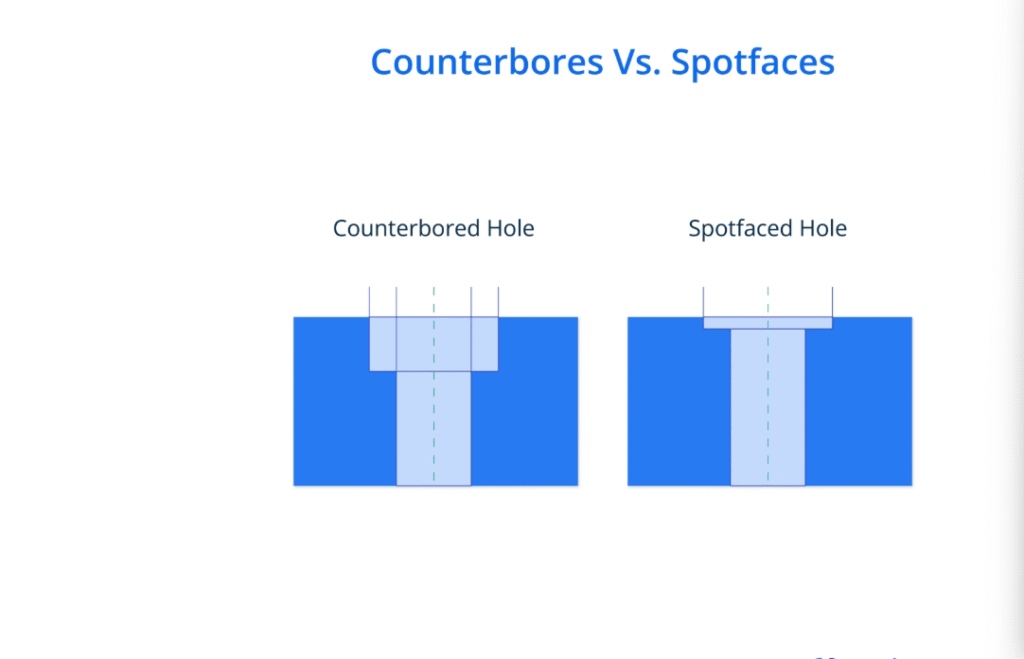

Counterbore Hole

cURL Too many subrequests.

Spotface Hole

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- Use counterbore when bolt head diameter is larger than screw shank

- Spotface rough surfaces to avoid uneven seating

- Consider counterdrills for complex fastening needs

Recessed holes help you get functional, flush surfaces that look professional and prevent hardware issues down the road. Knowing when to use each type saves time and improves your build quality.

Advanced and Irregular Holes For Complex Designs

When it comes to complex parts, plain round holes just won’t cut it. Advanced and irregular holes handle specialized needs like alignment, movement, and precise fits.

- Tapered Holes: These have a gradual change in diameter, often used for wedges or alignment pins. The taper ensures parts lock in place securely, common in automotive and aerospace assemblies.

- Interrupted Holes: Created by drilling partial sections with breaks or overlaps, these holes require multi-step processes. You’ll find them in gears or parts needing reduced weight but maintained strength.

- Slot Holes: Elongated openings that allow adjustment or orientation changes. Slots come with specific dimension specs and tight tolerances to keep parts precisely aligned during assemblies.

cURL Too many subrequests. For interrupted holes and other complex profiles, consider EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining) over traditional CNC milling. EDM excels with intricate shapes and hard materials where CNC may struggle.

These specialized holes add function and flexibility to designs, making them a must in advanced manufacturing and prototyping.

Hole Callout Symbols and Standards Reading Engineering Drawings

Knowing how to read hole callout symbols is key when working with any machined holes. These symbols communicate exact details like size, depth, tolerance, and surface finish right on engineering drawings.

GD&T Basics for Holes

Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) helps define controls like position, perpendicularity, and runout for holes. This ensures parts fit and function properly without guesswork.

Common Hole Symbols to Know

Here’s a quick cheat sheet of the most common hole callout symbols you’ll see, based on ISO and ASME standards:

| Symbol | Meaning | Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ø | Diameter | Basic hole size |

| ⊥ | Perpendicularity | Hole must be perpendicular |

| ⌴ | Countersink | Conical recess for flat-head screws |

| ☐ | Counterbore | Cylindrical recess with shoulder |

| ✓ | Spotface | Shallow flat surface |

| Depth Value | Hole depth (e.g., 0.5″) | Controls how deep a blind hole goes |

Be sure to check tolerances often—they control hole size limits and ensure parts mate correctly.

Common Pitfalls When Reading Hole Callouts

- Misreading depth: A blind hole might look like a through hole if you ignore the depth callout.

- Overlooking tolerance classes, which causes fit issues.

- Confusing symbols like countersink and counterbore.

Helpful Tip

Many shops now use digital drawing review services to catch these mistakes before machining starts. This can save time, reduce scrap, and improve part quality overall.

Reading hole callouts confidently ensures your machining matches design intent and avoids headaches down the line.

Applications Across Industries Real World Uses of Hole Types

Different hole types serve specific roles across industries, making them crucial for reliable and precise manufacturing in the U.S. Here’s how various sectors use holes to meet their unique needs:

AutomotiveClearance holes are common in engine blocks and chassis, allowing bolts and screws to pass through smoothly without threading the hole.

Tapped holes create strong threaded connections for components that need to be removable or adjustable, like cylinder heads and transmission parts.AerospaceTapered holes are often used for alignment pins, helping fit lightweight composite parts with tight tolerances.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests. cURL Too many subrequests. cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- cURL Too many subrequests.

- Plan for chip evacuation and coolant use.

Following these best practices will lead to better quality holes, fewer rejects, and smoother production flow.